When I was in third grade, my parents, who both worked in Washington, D.C., were finally able to build a house in their rural hometown of Marshall, Va. We had been living inside the beltway in an apartment, but they were willing to brave the commute from Marshall so that my sisters and I could be cared for after school by my grandmother, who lived down the hill. My one sister insists they made this move because someone tried to kidnap her, but I’ve never been entirely clear about that story.

As the house neared completion, someone needed to prepare the acre of surrounding land for grass seed, and that someone was me. Eight years young, I was handed a large contraption made up of eight two-by-fours nailed together in a square, with scores of long nails driven through them. This homemade plow attached to a long strap that went across my chest. For hours upon hours, I walked the length of what would become our lawn, dragging the two-by-fours behind me, the long nails breaking up the ground. In the years that followed, I would mow the grass that grew there for hours every week, along with doing landscaping and other chores for elderly neighbors for a few bucks.

Today, my son is responsible for mowing the postage stamp-sized patch in front of our home, for which I occasionally give him money. It takes him about 15 minutes if he does a really good job. This disparity between our childhood experiences might help explain why so many people my children’s age seem to measure racial progress by how offended they feel on any given day. It’s much easier to ponder your offenses when you are lying on the couch in the air conditioning.

If light manual labor played an irreplaceable role in forming my character, I understood it simply as part of growing up. Grownups worked, and if I wanted to be one, I had better start learning how. (Despite the relative lack of manual labor in the suburbs, my own kids have worked steadily from the time they were legally allowed to.) My grandparents did not have air conditioning or indoor plumbing until I was 10, but I never thought of them as poor. I loved playing at their house, although I was relieved to learn that the house my parents built did indeed have flushing toilets.

My idyllic childhood, surrounded by a large and loving extended family, did not mean that I didn’t see or experience racism. I heard the “N-word” as a matter of course. There was a restaurant in our town that refused service to blacks well into the 1980s. As children, my cousin and I were chased into the woods by a white man with a shotgun. (We had been throwing snowballs at cars, which was wrong. But even by the standards of the day, this was an overreaction.) My school guidance counselor told me not to take Latin (she said I would fail) and suggested that I enlist in the military instead of applying to college. At no time during my childhood did my parents, who attended segregated schools, or my grandparents, who did not even attend high school, say anything negative to me about whites.

Only later in life did I interpret my guidance counselor’s advice as a possible example of subconscious racial bias. At the time, when I brought the idea of joining the military to my mother, she informed me that I would not be enlisting and that I would, in fact, be going to college. Neither she nor my father had four-year degrees, but this was what they expected of me. I don’t remember it feeling like a burden, but I do remember that I trusted my mother’s opinion of my capabilities more than that of my guidance counselor.

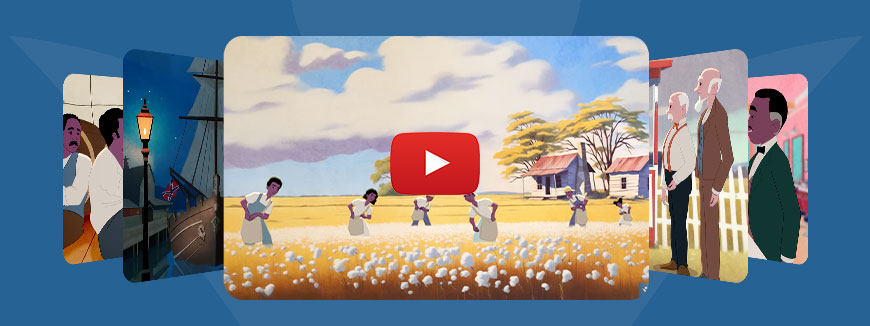

When I was younger, my mother had bought me a series of children’s biographies of black historical figures that included all the familiar faces: Martin Luther King, Jr., Harriet Tubman, George Washington Carver, and so on. But the one that caught my attention the most was Frederick Douglass, because two of the thin volumes were devoted to him. He must have been particularly important, I thought, to merit two books instead of one. And anyone who has read much about Mr. Douglass would agree that he packed at least two lifetimes of accomplishments into his 77 years.

What a man! Even as an elementary schooler, I could discern that he must have been a formidable figure. Every portrait of him — even the pencil sketches on the front my books — exuded dignity and demanded respect. Here was someone who taught himself to read, escaped slavery and went on to advise one of the most important presidents! If he began in slavery and accomplished all that, surely the possibilities for me were endless.

What I was learning from my parents, grandparents, from Mr. Douglass and all the other subjects of those biographies — without realizing it at the time — was how to deal with racism without losing my sense of who I was or absorbing racial insults into my soul. This is not to say that those who feel wounded by racism are to blame for their wounds. My experiences, including the ones I have had in adulthood, have been extremely mild compared to those of many of my friends. But I have also met many people who have experienced less overt racism than I have, who nonetheless feel haunted by the opinions of whites and hopeless about the prospects for black people in our country. Each new incident captured on video or splashed across the headlines causes them further despair. Why is this?

I was first introduced to something like the thinking behind The 1619 Project narrative when I was a freshman at Howard University in the mid-1980s. Never before had it occurred to me to process the racial slights I experienced as personal affronts. I knew they were wrong, of course, but I had never thought of “people being ignorant” as a serious injustice in need of correction. But I was a country boy, easily impressed by my more sophisticated urban peers. They seemed to know all this information about racism that I had never heard before. Their explanations of how difficult it was for black people to get ahead stirred feelings of outrage in me that I previously had not experienced. It was intoxicating.

When I went back home for the holidays that winter, I started viewing little slights in an entirely new way. The ignorant white people I encountered were no longer just harmless buffoons. They were now “powerful oppressors” holding me back and keeping me down. And somehow this new set of beliefs was supposed to combat the notion of white supremacy.

After getting better grades at Howard than I had gotten throughout high school, I transferred to the University of Virginia for my sophomore year. If I had been prone to develop an inferiority complex, the grades I earned that first year at UVA surely would have pushed me over the edge. The easiest response in the world would have been to conclude that my plummeting grade point average was just another link in the chain of white oppression that had kept my ancestors enslaved and my parents in segregated schools.

Instead — by the grace of God — I was able to dig into that same force that enabled me to break up that acre of fallow Virginia clay at 8 years old. I dragged my behind to the library for more hours each day than I previously had thought humanly possible. My aptitude for learning, thinking and writing rose, as did my GPA, and I graduated on time. In that process, I also decided that ignorant whites were no longer going to command my attention. I decided instead that I would do all I could to improve the situation of blacks in our country. I wanted as many black Americans as possible to enjoy the incredible advantages I had so far in life: faith in God, a loving, stable family, a good education and seemingly limitless opportunities to put it to use.

I am a grassroots guy, not a scholar, so I will not try to engage The 1619 Project from an academic point of view. What I can tell you is that I — and the thousands of African American pastors and leaders I am privileged to serve — learned in our schools the very “white history” that The 1619 Project seeks to remedy. Like me, most of the ministers I know had their public school education supplemented by additional black achievement-oriented reading material and black history-focused church events.[1] Like the books given to me by my mother, that material and events depicted black Americans as leaders who triumphed over adversity and made the country a better place, not as victims who led lives of tragic desperation.

Learning “white history” in school did not cause any of us to believe we were inferior to anyone, nor did we somehow naively conclude that the world was free of racism. The racism we did experience did not make us think that America and its ideals didn’t belong to us, nor did it deprive us of the ability to love our country and work to make it better. And thankfully we did not enter adulthood looking for pity or thinking of ourselves as helpless pawns in a white man’s world.

My organization, named for Frederick Douglass, works on issues of importance to black churchgoers, which include strengthening the black family, supporting criminal justice reform and securing economic and educational opportunities for all. In our work on the black family, we have found that there are two opposite dangers that black parents must avoid when teaching their children about race. We cannot raise our children to think that racism does not exist or not to value and embrace their race as part of their identity. Black Americans will always encounter at least some people who see their race before they see anything else, and we have to prepare our children for those encounters in a way that minimizes the likelihood that they will be traumatized or endangered.

However, we also must avoid rearing kids who see every setback they face through the lens of race and look for opportunities to be offended or outraged. This is what The 1619 Project is in danger of encouraging, and had I continued to embrace such a message in my youth, I never would have graduated from UVA. I personally think it would be more helpful if we could regularly separate the problem of racism — individual and systemic — from the problem of racial inequalities. Eliminating the first, were that possible, would not eliminate the second. That doesn’t mean people shouldn’t try to be less racist, but they should not deceive themselves to think that in so doing they are saving most black people from anything other than annoyance.

The problems that exist in a portion of the black community will not be solved, or even ameliorated, by a widespread embrace of The 1619 Project. That does not mean that the way we teach American history couldn’t be improved. Black Americans — great and ordinary — have achieved incredible things against formidable odds, for themselves and for our country from the time of its founding. The fact that we have been able to embrace the principles of the American founding, despite the hypocrisy with which those principles were first applied to us, should testify to their power, not justify their weakening or destruction. Freedom and progress require work. And each of us must be willing to pick up our own plows and work until our job is done.

[1] I am proud to say that my own Black History Month presentations have improved considerably from the time I stood holding up a hand-drawn poster depicting slaves fleeing servitude on the back of a pickup truck.