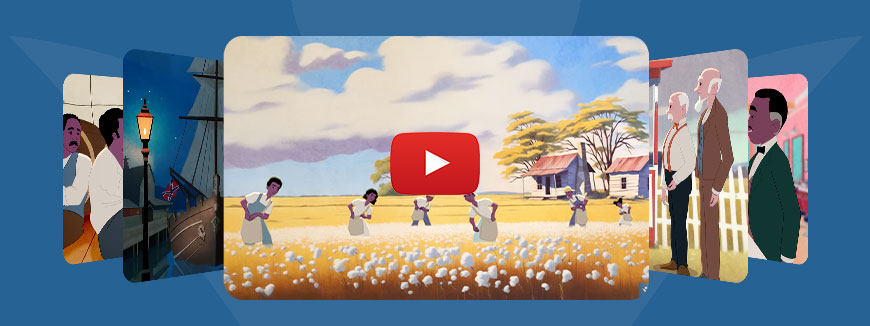

Blackness is an idol now. It is worshipped. The black race is the “Black” race now, according to the New York Times, the Associated Press, and other media outlets. And “Black is King,” according to the title of Beyonce’s new musical film that will stream this week on Disney Plus. Beyonce is an artistic genius and I will not judge a film I’ve yet to see, but the title is peculiarly provocative for Disney. It seems rather tone-deaf in a pluralistic society.

My main concern, however, is not with what non-African Americans think about how we express our identity, but about how our self-identity impacts our growth as a people. “Black is King” seems to be a nod to African and African American greatness, or as Beyonce describes it, “the beauty of tradition and Black excellence.” But appeals to “black greatness” without acknowledging the importance of morality can lead us away from the human freedom and advancement our ancestors struggled for, if we’re not careful. It may be unpopular today to question these assertive expressions for self-esteem, but my own personal journey urges me to do so.

As a teenager in the late 1980s and early ’90s, I was hyper-focused on race and blackness. In high school, to demonstrate my militant love of black identity, I regularly wore a black jacket and a black leather baseball cap with a red, black and green Africa pin on the side. It was the golden age of hip hop and I loved writing rap lyrics. My signature rhyme back then was called, “Raise your mind to Blackness.” Looking back, I see that time as an important period of awakening for me, when I gained an appreciation of my heritage and developed greater awareness of the historical and contemporary struggles of the African American situation.

This emphasis on black pride was my counterweight to address the remnants of racism I saw in 1980s and ’90s America. Some of those remnants manifested as incidents close to home, such as the Rodney King beating, which occurred a few blocks from my house at the time. Much of it was from what I viewed on television, such as the famous Oprah Winfrey show episode in 1987, when Oprah visited a Georgia county that had banned African American residents since 1912.

In reaction to such realities, I embraced a “too black, too strong” identity. Like many teenage awakenings, the orientation I took on was a bit imbalanced. I’m thankful for the growth of that period, but it came with a cost. Blackness became my barometer for what was correct, what was worthwhile, and what was good. I would never have used these words at the time, but what I embraced was essentially a morality for ethnicity. There is a fine line between appreciating your culture and being obsessed with it.

Something changed by the late 1990s to help me evolve. After years steeped in what was essentially a worship of my race and culture, I went through a new awakening, a spiritual one. I had been reading an English translation of the Qur’an daily, contemplating converting to Islam. At one point in my reading, I reached a verse that said:

“O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you races and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of God is the most righteous of you.” (Qur’an 49:13)

It was a seminal moment. Instantly, and for the first time, I began to question a longstanding assumption I held — that, because of the existence of anti-black racism in the world, black racial pride was a sufficient and noble goal by itself. But those Quranic words challenged that notion. They conveyed quite elegantly that race, culture and heritage had little value when detached from morality. Culture could be beautiful, but it was utilitarian and meant to help us orient ourselves evenly with other cultures and peoples, all under God. I was humbled.

Making black our “king” reminds me of when I urged my high school friends to “raise their minds to blackness.” It was a push to pride without any prescription of conduct. But this is more problematic today than in my youth. In the ’80s and ’90s our pro-black assertions and call-outs of racism were not mutually exclusive to reminders of personal conduct. Consider two popular hip hop songs of that era, “We’re All in the Same Gang” and “Self-Destruction.” The biggest rappers of the day came together on those records to discourage black-on-black crime. Also think about Boogie Down Productions’ “Love’s Gonna Getcha,” which narrates the story of a young African American whose love of material wealth leads to his rise as a drug dealer, violence against his family, and his eventual death or arrest.

Today’s popular African American thought leaders would frame such messages as nothing more than blaming the victim and pandering to so-called white supremacy. Yet, back then, we could criticize “the system” and our own community members’ actions without being denigrated. Now, most of our cultural expressions of social consciousness emphasize only the outer circumstances and stay mute on our inner conduct. Both conservatives and liberals are vulnerable to backlash. As far back as 2013, President Obama drew heat from voices in the African American community for telling recent Morehouse University graduates to make no excuses for themselves and embrace personal responsibility as they went out into the world.

It is a shame that our African American intelligentsia reflexively eschew any appeal to morality as misguided “respectability politics” and frame it as an attempt for elusive white acceptance. However, self-respect, if it means anything, has little to do with how others see you. And it is odd since it is undeniable that religion with strong moral codes was central to African American progress throughout our centuries-long struggle for freedom. Our ancestors who were the most successful in building African American justice, education and empowerment were believers in religious scripture, and thus valued a self-identity beyond their skin color, even when their color was central to their struggle.

Frederick Douglass was not struggling for blackness. He was struggling for blacks, influenced by what he called “the Christianity of Christ” that he read in the Bible, rather than the warped version he experienced in slave-holding America. Harriet Tubman was not emboldened to free people by her blackness. She was emboldened by her deep belief in God to take the risks she took. Marcus Garvey, well-known for spurring thousands of followers toward racial unity, pride and self-determination, was what might today be called “unapologetically Christian.” His “Back to Africa” movement had a strong missionary component that later pan-African admirers dismissed.

As a Muslim, I see a parallel in the role of my faith in our history. Many do not get how our Muslim African American leaders of the past were pushing for a universal, moral identity. Malcolm X is characterized one dimensionally for black nationalism, but he despised the term “Black Muslim,” even when he was building the Nation of Islam. He stressed this in his autobiography, commenting on how the news media wrongly latched onto the term “Black Muslims”:

“The public mind fixed on ‘Black Muslims.’ From Mr. [Elijah] Muhammad on down, the name ‘Black Muslims’ distressed everyone in the Nation of Islam. I tried for at least two years to kill off that ‘Black Muslims.’ Every newspaper and magazine writer and microphone I got close to [I told]: ‘No! We are black people here in America. Our religion is Islam. We are properly called ‘Muslims!’’ But that ‘Black Muslim’ name never got dislodged.”

Malcolm in both his Nation of Islam and post-NOI days tried to help African Americans tap an identity of an inner nature, which is difficult to do when using terminology that emphasizes something solely external, such as skin color. Though the Nation of Islam pushed an idea of black supremacy, its catechisms taught that black people’s true nature that they must rediscover was that of a “righteous Muslim.” Nobility was not in color by itself. It is noteworthy that after his pilgrimage to Makkah, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabbaz started a group which he named the Organization of Afro-American Unity, not the Organization of Black Unity.

And after NOI leader Elijah Muhammad died in 1975, his son Imam W.D. Mohammed was selected to lead the movement. He then directed his following to embrace universal Islam and steer away from color language. For a brief time, the former NOI community called itself “Bilalian,” in honor of Bilal ibn Rabah, the brown-skinned Abyssinian who embraced Islam as a slave, became free, and was a beloved companion of Muhammad the Prophet. Imam W.D. Mohammed’s association emphasized that they saw themselves simply as Muslim Americans and would specify “African American Muslims” only to be precise when necessary. Color-focused nomenclature was rejected, as was a race-based worldview.

How times have changed in a short period! It is not insignificant that “black” has overtaken “African American” as the media’s preferred descriptor of Americans with recent African ancestry. “Black” conveys a subtly different spirit, rooted in the topical aesthetic and serving as a binary opponent to “whiteness.” Still, the phrase “Black is beautiful” is passe now. That self-esteem-invoking mantra seemed necessary in an era when Beyonce’s or Lupita Nyong’o’s beauty would be uncelebrated by America’s mainstream media. But today’s mantras are provocative hashtags and memes. Our new generation asserts that they are unapologetically #BlackAF, because they don’t give two F’s what you think about their blackness.

I am sure “Black is King” will be a stunningly beautiful exposition of African and African American culture. But I wonder what it will point us toward. My worry is that it will call us to find nobility attached so much to our color, when that is the most superficial aspect of ourselves. I am concerned it will urge us to think of our culture as honorable, but with no standard beyond aesthetics. Black pride is certainly an important part of our growth. But if it is all that guides us, we certainly will be stunted.

Yaya J. Fanusie is a consultant and researcher on national security policy and financial technology. Before working for several years as an analyst at the CIA, he taught mathematics at a Washington, D.C., high school and also worked briefly in D.C.’s juvenile detention system. He produces a podcast that features African American Muslim storytelling called “Rhythm of Wisdom.”

Copyright 2020 The Woodson Center