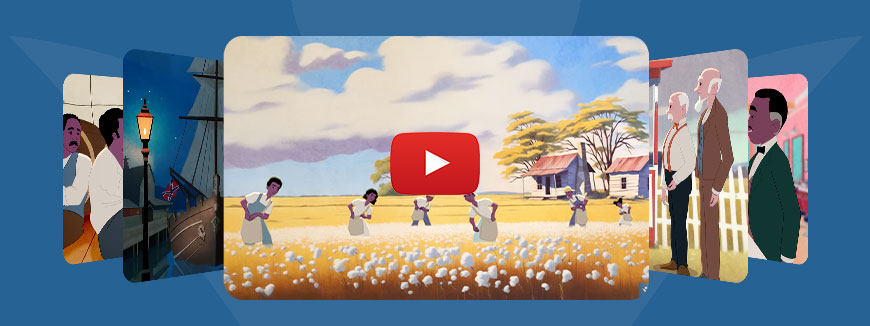

In 2019, marking 400 years since the first known Africans arrived on these shores from West Africa as slaves, the New York Times launched its ambitious 1619 Project. It aimed to reexamine U.S. history through the lens of black history — as if American history began with the arrival of the first black folks.

The concept was well-intended, and the execution of its first episode well-documented. Yet, it left me feeling that the New York Times missed at least half of the story. By looking through the lens of black victimization, it paid too little attention to what I call “black overcoming” — our victories over adversity and achievements of success, sometimes in conflict but also often in cooperation with people from other races and ethnic groups.

The New York Times incorrectly assumes that the challenges facing particularly inner-city blacks are related to a legacy of slavery and discrimination. This is patently untrue. Let’s look at the issue of poverty and how we’re treated.

Our perceptions are distorted by the “colorization of poverty” in the mid-1960s. Media images of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “war on poverty” focused mostly on poor whites in Appalachia, where LBJ announced his initiative — and where I later would work with mostly white teens in the Upward Bound program as a college student in 1967. But with the outbreak of riots in Watts, Harlem, Chicago, and other urban centers, news media images of rural poverty were replaced by images from the “ghetto.”

Colorization has had a profound impact on other issues too. In the 1980s, for example, crack cocaine was perceived as a mostly black problem and a law enforcement issue. In the 1990s, opioid addiction was perceived as a mostly rural white problem and a public health issue.

J.D. Vance, writing in Hillbilly Elegy about growing up in the same Ohio town where I had grown up almost two generations earlier, ignited a new discussion from the grassroots of white poverty and drugs that showed me the important similarities between poor blacks and whites in America, despite the tribalism encouraged by demagogic leaders in both races. “I have known many welfare queens,” Vance writes. “Some were my neighbors, and all were white.” His candor is refreshing.

Vance tends to view poverty in the way many people in the traditionally Republican town of Middletown, Ohio, as a problem of culture, morality, character, and personal responsibility. I agree that personal character matters, but I also have witnessed those values undermined by what William Julius Wilson called “the disappearance of work” — of Ohio’s well-paid, low-skill industrial jobs that lured Vance’s family from Kentucky and mine from Alabama.

Vance’s book forced me to take a new look at my life and hometown and about our similarities and our differences. Vance explains in his introduction to how personal stories offer cultural insights that are essential to any serious discussion of equal opportunity.

“Nobel-winning economists worry about the decline of the industrial Midwest and the hollowing out of the economic core of working whites,” he writes. “What they mean is that manufacturing jobs have gone overseas and middle-class jobs are harder to come by for people without college degrees. Fair enough — I worry about those things, too. But this book is about something else: what goes on in the lives of real people when the industrial economy goes south. It’s about reacting to bad circumstances in the worst way possible. It’s about a culture that increasingly encourages social decay instead of counteracting it.”

It’s not laziness that’s destroying hillbilly culture, says Vance. It’s what psychologist Martin Seligman calls “learned helplessness.” Too many of us African Americans have picked up that malady as well.

Where should we go from here? Similarities between Vance’s life and mine showed me how much we need to desegregate our poverty discussion, to learn across the lines of race and class the true causes of poverty and inequality — and, more importantly, what works to solve them.

Yes, blacks have fought to make true the ideals in our nation’s founding documents, as the New York Times says. But its statement that the “founding ideals were false” is misleading and even counterproductive to our understanding of the founding documents as aspirational. The principle that “all men,” or people, “are created equal” was true in early American law only for white, property-owning men. But the Founders, as a minority themselves, wisely took that principle of equality very seriously in the abstract, understanding that they themselves might need it someday. They established a tradition: Guarantee “inalienable rights” to some but also establish the legal mechanisms to extend those equal protections to others without — and this is important — taking those rights away from those who have them.

Our project, “1776,” puts less of an emphasis on history and more on the question prophetically raised by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., at the height of his civil rights revolution: “Where do we go from here?” Mindful of the inevitable criticism that his movement was subversive, King made a special effort to ground his historic 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech in “a dream as old as the American dream” by repeated references to the nation’s founding documents, including Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.” He assured friends and foes alike that his civil rights movement had come not to deny the gospel of the American dream, but to fulfill it.

We must disrupt the long-held stereotypes of black people as helpless bystanders in their own history. We have had entrepreneurs, skilled tradesmen, military officers, inventors, organizers, and many others who responded to adversity by marshaling resources, building local enterprises, and creating jobs. We organized and acted to defeat slavery, segregation, and deprivation, and then we persevered to build businesses that included banks, hotels, small factories, and a black-owned railroad.

In addition to the consequences of slavery, these contributions of black Americans should be at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are. Even in bondage, slaves had agency in various amounts, or to varying degrees, and they acted on it in a variety of ways. Those who prefer to focus on our victimization don’t always want to recognize it, but the ways our ancestors exercised agency in bondage formed the foundation of their successes (or failures) after they were freed.

Americans are optimistic people, but we care more about the future than the past. We care about the past mostly as much as it helps us to deal with the uncertainties of our future. Changes, demographic and otherwise, are tearing us apart. Our historic victimization must never be forgotten, but it is best remembered through the stories of our groundbreaking victories over oppression through faith, courage, talent, persistence, ingenuity, and hard work.

It may be a cliché these days to note that our differences should not be allowed to stand in the way of what we share in common, but too often they still do. We must find ways to appreciate the contributions that our diverse population contributes to American life. We need to study not only the atrocities of U.S. history but also America’s magnificent capacity for self-improvement as we seek the tools and knowledge to help us face our shared future with new hope — together.

Pulitzer Prize-winning news columnist Clarence Page is a columnist and television commentator with a journalism career now entering its seventh decade. He is a senior member of the editorial board of the Chicago Tribune, where he publishes new columns that go up online every Tuesday and Friday.